Challenges in a multi-cultural team? Here there is something you can do

I worked for years with teams that had people from all over the globe. Often I found myself thinking about the cultural implications of bringing people from so many different places together. Sometimes organisations tend to push the company culture to override local cultures, and I think that’s a mistake. It shouldn’t be about forcing a common culture but creating that common space where all cultures can live together and people feel secure and can perform at their best.

The Culture Map, a powerful reflection and tool for team collaboration

Luckily, I wasn’t the only one (nor the first one) to think about this challenge. Erin Meyer published on 2014 her book “The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business” where —through engaging, real-life stories and anecdotes— she explains a field-tested model for decoding how cultural differences impact international business.

“Company culture is the continuous pursuit of building the best, most talented and happiest team we possibly can.” — Andrew Hilkinson

Erin explores cultures based on 8 different dimensions:

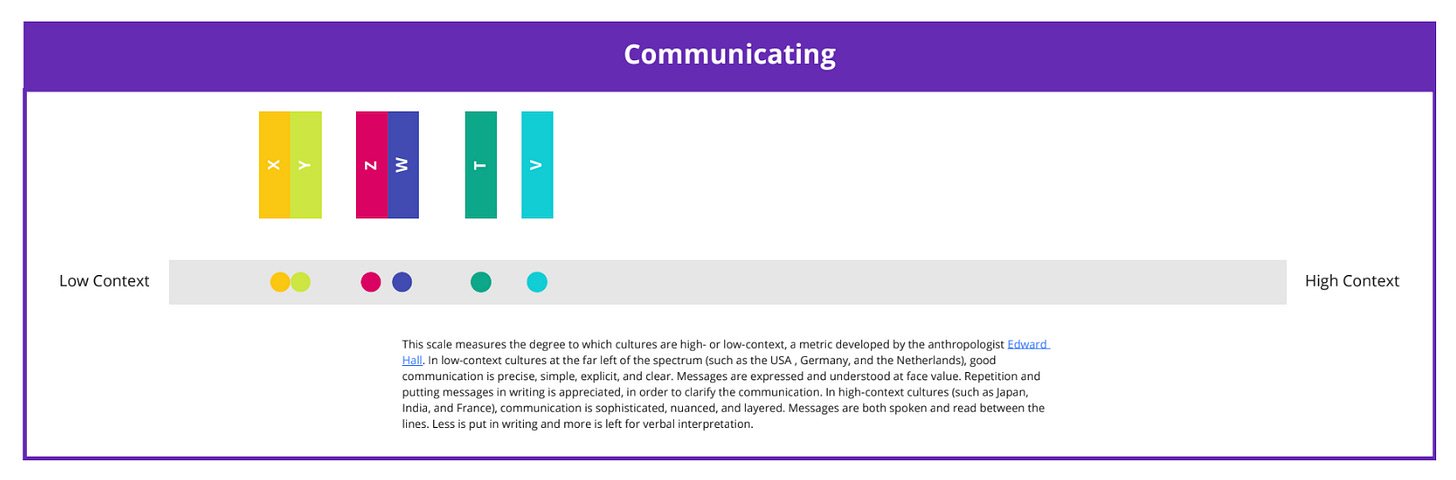

Communicating (Low context to high context): This scale measures the degree to which cultures are high- or low-context, a metric developed by the anthropologist Edward Hall. In low-context cultures at the far left of the spectrum (such as the USA , Germany, and the Netherlands), good communication is precise, simple, explicit, and clear. Messages are expressed and understood at face value. Repetition and putting messages in writing is appreciated, in order to clarify the communication. In high-context cultures (such as Japan, India, and France), communication is sophisticated, nuanced, and layered. Messages are both spoken and read between the lines. Less is put in writing and more is left for verbal interpretation.

Evaluating (Direct to indirect negative feedback): This scale measures a preference for frank versus diplomatic criticism. It is often confused with Communicating, but many countries have different positions on the two scales. The French, for example, are high-context communicators relative to Americans, yet they are much more direct when it comes to negative feedback. The Spanish and Mexicans are equally high-context, but the Spanish are much more direct with negative feedback than Mexicans.

Leading (Egalitarian to hierarchical): This scale measures the degree of respect and deference shown to authority figures, placing people on a spectrum between the egalitarian and the hierarchical. The former include the US and Israel, while countries such as China, Russia, France, and Japan are hierarchical. The metric is based on the concept of power distance, first researched by Geert Hofstede, who conducted 100,000 management surveys at IBM in the 1970s, and on the work of Professors Robert House and Mansour Javidan in their "The Globe Study of 62 Societies.".

Deciding (Consensual to Top-down): We often assume that the most egalitarian cultures in the world will also be the most consensual, and that the most hierarchical ones are those where the boss makes unilateral decisions. This is not always the case. The Japanese are both strongly hierarchical and one of the most consensual cultures in the world. The Germans are more hierarchical than Americans but also more likely to make decisions through team consensus. This scale explores differences between building team agreement and relying on an individual (usually the boss) to make decisions.

Trusting (Task-based to relationship based): Here we balance cognitive trust (from the head) with affective trust (from the heart). In task-based cultures, like the US, Britain, and Germany, trust is built through work. (We work well together, we like each other’s work, we like each other so I trust you.) In a relationship-based society, like Brazil, Japan, or India), trust is a result of weaving a personal, affective connection. (We have laughed together, shared time relaxing together, gotten to know each other at a deep personal level--so I trust you.) Many scholars, such as Roy Chua and Michael Morris, have researched this topic.

Disagreeing (Confrontational to avoid confrontation): Everyone knows a little open disagreement is healthy, right? The recent American business literature certainly confirms this viewpoint. But different cultures have very different ideas about how productive confrontation is for a team or organisation. Counties like China, Japan, and India view the public airing of disagreement very dimly, while the US, France, and the Netherlands are quite comfortable having spirited, confrontational meetings. This scale measures how you view open disagreement - whether you feel it is likely to improve team dynamics or negatively impact team relationships.

Scheduling (Linear to flexible time): All businesses follow timetables, but in some cultures such as India, Brazil, and Italy, people treat the schedule as a suggestion, while others stick to the agenda (such as Switzerland Germany, and the USA). This metric looks at how much value you place on being structured versus reactive. It is based on the "monochronic” and "polychronic” distinction formalized by Edward Hall1.

Persuading (Principles-first to application-first): This scale measures a preference for inductive versus deductive arguments. Individuals from Southern European and Germanic cultures tend to find deductive reasoning more persuasive whereas Americans and British managers typically prefer an inductive style.

The Culture Map Workshop

Let’s start with a short story and a bit of context. The story is real but not the names for privacy reasons. Let me introduce you: Mathew, a business manager that was responsible of a multi-cultural team with people from Germany, France, UK, Italy, Spain and Poland. He approached me, an Agile Coach, because the team was suffering from “not being understood” nor by the manager nor by the peers.

Mathew and me got together with the team to explore what was going on, and at some point I mentioned the Culture Map. Instantly there was light at the end of the tunnel and people expressed the curiosity and the motivation to try something with it.

So this is how we made it:

Each team member and the lead took the culture map assessment that you can find at the official site: https://erinmeyer.com/tools/culture-map-premium/. It is not free but the price is affordable and the results are worth.

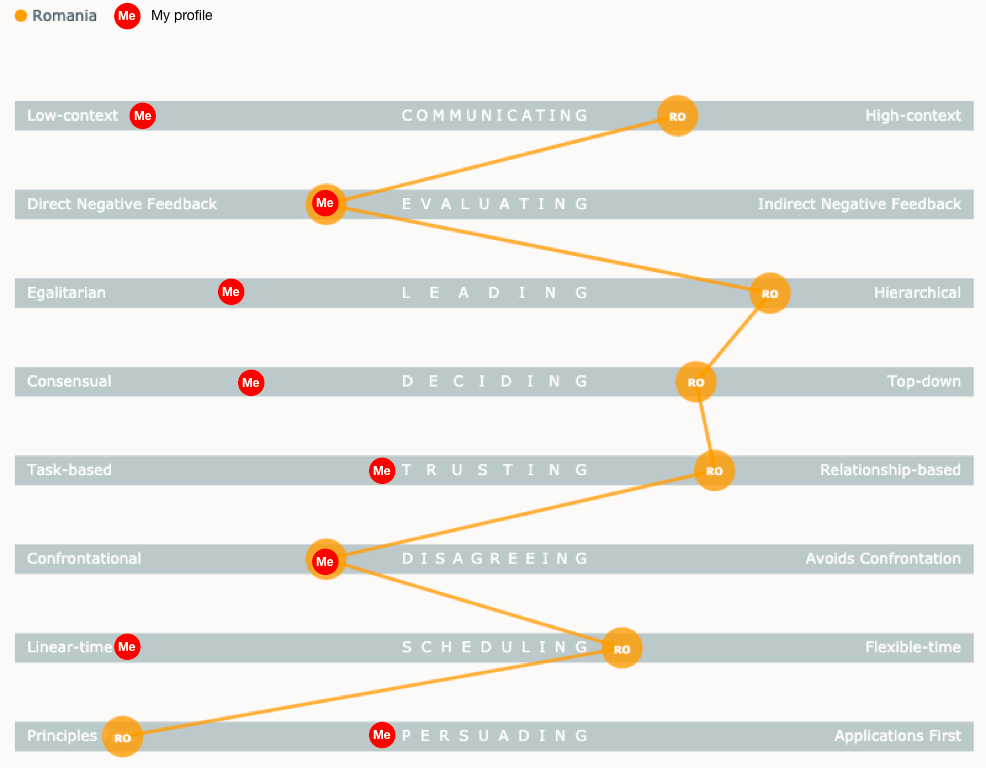

Each participant sent me (the Agile Coach) the picture of their results. An example is the following one:

In our case the results of the individuals compared with their country results are not meaningful. So, we take the personal results (me) and generate a workshop in Miro (A digital whiteboard tool that allows you to co-create and do workshops online) exposing the results of each participant together.

Finally and the most important part, we discussed about the results. The important rule in this part is that we were not trying to change anyone’s culture. We were trying to understand and arrive to collaboration agreements in order to let everyone perform at their best as individuals and more importantly as a team.

As a last step on the workshop I asked for the ROTI2 (Return of time invested) and it was pretty high! Also discussing some weeks after the workshop with Mathew, the workshop changed the trend of the team and they were collaborating better than ever. And in the end, this is what really counts.

In case you are interested here you have the entire workshop PDF extracted from Miro.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_T._Hall

https://www.teamretro.com/return-on-time-invested